Pragmatism and Adaptability: The Essential Behaviours for Any Strength and Conditioning Coach

- Shahbaz Hasan

- Apr 12, 2018

- 6 min read

Updated: May 12, 2018

Who can remember being a new strength and conditioning coach? Do you remember what you thought the world of strength and conditioning would look like? I remember in the early 2000’s, I would think how awesome it would be to work with these super motivated highly talented athletes, in state of the art facilities, with all the scientific gadgets you can imagine and top of the range equipment. Then reality hits you, the majority of strength and conditioning environments are very different. It is common place for us coaches to have to manage with many limitations within these training environments including lack of equipment, lack of time, lack of financial backing by the club and a lack of athlete motivation. These are but a few of the challenges a coach could face, however these could be infinite and they threaten to compromise the coach’s effectiveness. As such, this article focuses on the coaching behaviours of pragmatism and adaptability, which in my opinion are two indispensable qualities every coach should attain. At the end of the article a framework will be presented detailing how to plan training periods using these behaviours.

The training environment is a chaotic environment which is constantly changing, if you consider that the coach is trying to elicit positive adaptations within numerous athletes all who come with their own specific make up physically and psychologically as well as resource, time and financial resource scarcity, chaos is almost inevitable. Within this chaos is a great deal of uncertainty, as we are unaware what problems/ scenarios the environment will present for a given training session that the coach will have to manage.

The majority of our industry I think is biased towards certainty or stable environments. Two main areas where this is apparent is if you observe the majority of commentary on the internet or the scientific literature. Many of the conversations are dominated by biomechanical, physiological or general training theory and how particular athletes have got better by traditional strength and conditioning strategies such as a certain type of periodization, monitoring protocols, a particular drill or through specific kinematic/kinetic alterations.

A large assumption which exists within these conversations is stability of the environment in that the only aspect that made a difference to the outcome was the training intervention or aspect being discussed rather than an appreciation of the wider environment. Additionally, very few strength and conditioning interventions are instant with a requirement for continued stressors or practice over time which brings further unpredictability to these scenarios. The reality is many different constraints, presenting themselves on a daily basis which the coach has to manage. It is folly to think that we could devise strategies for every single scenario that presents itself as these could be infinite, however what may appear to be more useful is if we use effective coaching behaviours, namely to be adaptable and pragmatic in the situations we find ourselves in.

In being pragmatic I believe the coach should be asking themselves this question “what is the simplest way for me to achieve the outcome I am looking for, with a minimum outlay of resources”.

This statement has two further imperatives, namely that the coach should have a deep understanding of how adaptation occurs and have optionality within their methods. While the notion of understanding adaptation may appear contradictory to my prior statement on literature, this should be used to understand the mechanism of how adaptation occurs in the quality the coach is seeking. Specific modalities described in literature/ training theory may or may not be useful, however the ability to impact the underlying mechanism is important in delivering favourable outcomes. The coach can then use this knowledge to understand what are the most important aspects to drive, and can also use this knowledge if further constraints present themselves. As an example, if the coach is dealing with a cohort of athletes with poor motivation seeking hypertrophy adaptations, the main aspect to drive within this scenario would be overall volume of work. While this may appear overly simplistic, the key to this scenario would be to engage and motivate the athletes in completing the work, as such all the coach would need to consider from a mechanism point of view, would be to acquire enough volume.

The second imperative within this pragmatic approach I believe should be optionality of methods. If the coach only has one way that they can improve a certain quality, they are at risk of facing a situation where this strategy would be inefficient or inappropriate. Consider the same scenario as above where a coach’s only method was to use highly structured sessions with very specific prescription to achieve hypertrophy. As the athletes are poorly motivated it is unlikely the session will be completed at the effort levels that are appropriate and would compromise the adaptation sought. What would be more relevant is to create a engaging environment where athletes are motivated to put forth high effort, the acute programming variables would simply need to ensure enough volume is accumulated.

The second coaching behaviour that is key in managing chaotic environments is that of adaptability. This behaviour also has two imperatives, that being to understand the athletes and environment as well my previous notion regarding numerous methods to achieve outcomes. The reason a through understanding of the individuals and environment is key is that it allows an informed guess of what may happen. Ultimately, the success of a session is based on the individuals interacting with the environment in the context of the task they are completing. As such if the coach has a good appreciation of both these aspects the task can be formulated considering the dynamic between task, environment and athletes.

In understanding the athletes, the coach should know their athletes well and understand how they may react to particular scenarios. For instance, if a coach is wishing to train agility within a particular cohort of athletes who have poor discipline it may be a better strategy to use closed agility drills where the environment is more predictable and there are specific outcome goals, whereas for well disciplined athletes chaotic drills with higher unpredictability would be more relevant. Secondly, the coach should understand the training environment. This is more than simply the physical nature of the environment but how the athletes perceive the environment and what behaviours this may elicit. As an example If the coach decides to play music within weight room sessions will this elicit higher motivations from the athletes or will it reduce focus with the athletes focussing too much on the music?

It should be noted that while an understanding of athletes and environment would allow some level of predictability, it would be almost impossible to understand these aspects fully due to the dynamic and sensitive nature of them. As such, an appreciation of these aspects would allow a somewhat informed guess on how each element of the training environment will interact with each other.

Although much of this article has talked about how a coach can use adaptability and pragmatism to essentially plan sessions and achieve more predictable outcomes, one key aspect we have not mentioned is that of how the coach will interact with the environment. While this is outside the scope of this article, the coach’s behaviour within sessions will have an impact on the athletes behaviour and the environment and will be key in delivering outcomes. Coach’s should be mindful of this aspect and elicit behaviours that are appropriate for the training situation they find themselves in.

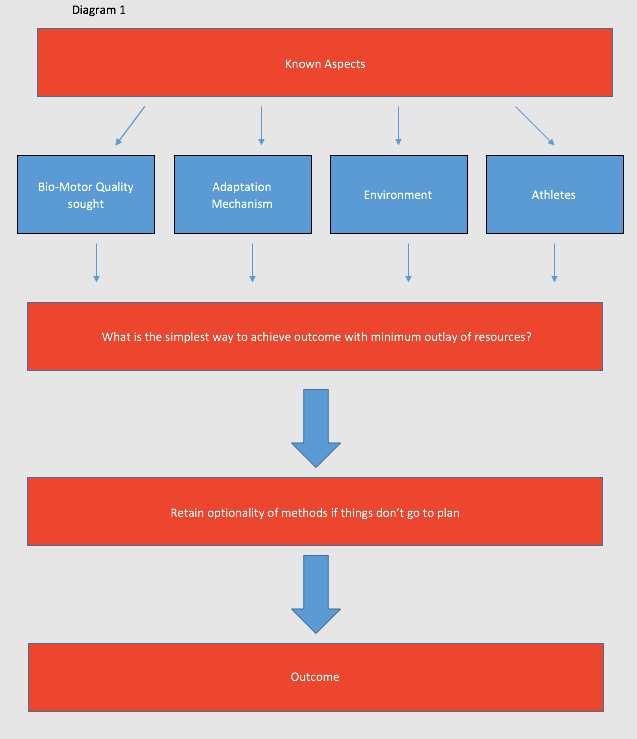

Using the behaviours of pragmatism and adaptability, training periods could be planned on what is known (athletes, environment, adaptation theory) and what potentially could go wrong (optionality of methods) (diagram 1). The benefit of using this framework is in its comprehensiveness and compared to traditional planning strategies uses numerous considerations to derive the best approach. However, coaches should remain aware that although better decisions can be made by using the framework, many aspects will remain unpredictable due to the dynamic aspects involved. As such a coach should not look at this framework as an absolute certainty of what will happen but a guiding tool in assisting them to make informed decisions.

In summarising, the ability to be pragmatic and adaptable is key to allow a coach to be effective at driving adaptations within an ever changing environment. The coach should have a good understanding of the theoretical nature of adaptation, as well as a good understanding of their athletes and how they will perceive the environment to allow some level of predictability along while considering their own behaviour. Finally, the coach should strive to attain numerous methods by which to achieve adaptations which allows them the ability to manage different environments and athletes.

Comments